Growth Fundamentals: 6 Actions to Prevent Wasting Money with SEM

Search Engine Marketing, or SEM, is a significant piece of the growth puzzle for many businesses. It’s the way you “scoop up” the demand from customers ready to buy; the efficiency of your advertising spend very much depends on getting this area right. And yet, it’s quite hard: it’s technically complex; incentives of the ad platforms make it easy to waste lots of money - while being convinced of how great SEM is.

In the past few years, I had a chance to help a dozen consumer businesses accelerate their growth. In a series of blog posts, I’m sharing stories about the kinds of problems that, after solving, were “visible from space” for the financial outcomes of the relevant businesses.

This one digs into paid search, also known as Google SEM. Here are some tips.

1. Run the searches yourself, be the customer!

Run a few searches that your customers are running. Look at what the ads say. Look at the pages where you land. You might just be surprised. Having worked with otherwise tremendously successful D2C brands, I find that “dogfooding” regularly - acting like a customer would - is a great way to avoid unforced errors.

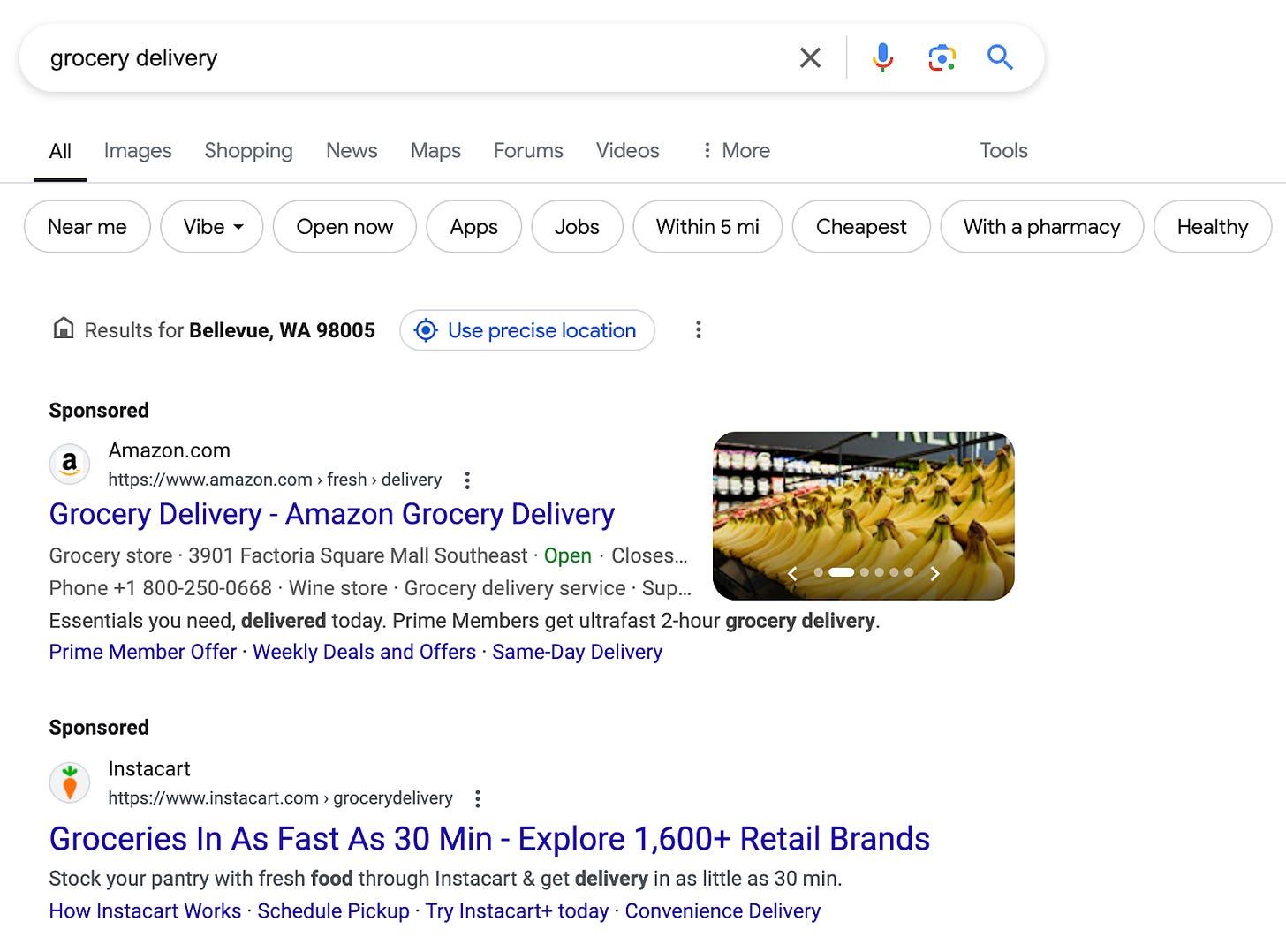

The most basic failure mode is the mismatch between the search term and the copy of the ad. The copy of the ad is something that you fully control; your ad needs to include points of differentiation - and reasons to believe - that will get your prospect to click. For example, in response to “grocery delivery” search query, Instacart’s SEM ad rightly focuses on “delivery in 30 mins” and “1600 merchants.” Amazon Grocery ad just says “Prime members get ultrafast 2 hour delivery”... It’s not really a favorable comparison in the context of what their chief competitor is offering.

An even more frequent mistake that I see is a mismatch between what the landing page shows versus what the ad promises. For example, the ad promises iPhone cases; the landing page shows a collection of Apple accessories - cords, screen protectors, etc; and iPhone cases as a small subset. Or, the keywords the customer searches for are about a specific health condition; the landing page doesn’t even mention that health condition.

Another failure mode that’s easily discoverable if you’re willing to act like the customer: observing inventory mismatches. Your top selling product on Google Shopping can easily become a money drain if the most popular variations (sizes, flavors, etc) are sold out: Google will keep sending customers to your site (at your dime) while conversion rate rapidly deteriorates. If you use a feed management tool like Feedonomics, you can set up rules that hide specific items from your ads if their most popular sizes are sold out.

2. Understand the incrementality of your branded search ads

When reviewing the effectiveness of your marketing spend, you will likely find a line item that seems too good to be true: branded search. The CAC for it will be much lower than all other channels. That’s your ads that show up when customers are searching for your brand name. These customers obviously have very high intent. Your branded search ad is a perfect match to their query; so cost per transaction that you’re paying Google is quite low.

Intuitively, though, some portion of the customers searching for your brand name would have converted anyway, even without the ad. Right? You’re ranking high organically for your own brand name (hopefully, #1). At least some - if not most - searchers would click on your organic listing and buy from there, even if you didn’t have a branded search ad. That is, the incrementality of this spend is suspect. It’s even more likely that this spend is wasteful if no competitors are bidding on your brand terms.

How can you find out what the incrementality really is? Run a test: turn off branded search for a period of time; observe how much organic search picks up; turn it back on and observe how much organic drops. The missing conversions is the real incrementality of your branded search campaigns.

Having run three incrementality studies for branded search in the past couple years, I’ll give you a benchmark: 80% of customers would convert without your branded search ads. That is, whatever Google is telling you is the CAC of acquiring customers via branded search… multiply that by 5.

Be particularly careful in the new world of Performance Max, or PMAX, that Google has been forcing advertisers in the past few years. PMAX is a black box; proceed with caution due to the complete lack of control and make sure to leverage a data feed when applicable. Check queries to make sure PMAX is driving non-brand traffic. Without specifically adding brand negatives, PMAX is almost always entirely branded traffic, which, as we discussed above, is barely incremental.

3. Set bids using the lifetime value of customer segments

Paid search allows you to “scoop up” the demand at the bottom of the marketing funnel. The problem is, not all demand is identical - and different customers searching for different things will vary tremendously in terms of their worth to your business.

Let’s look at some examples.

Imagine you’re selling women’s clothing. Somebody searching for a “mom and daughter matching dress” is probably going to be buying two dresses… so all other things being equal, you should bid higher on this term. Somebody searching for “best discount for women’s dresses” is probably someone who will not buy your highest-margin item… bid less for them.

Imagine you’re doing grocery delivery. Some customers are going to be very valuable: suburban moms doing the grocery shopping for the whole family for the whole week. Bid more to capture those customers. Some customers, less so: ex. urban 20-somethings trying to buy some mac and cheese to fill up their fridge.

There are technologies within various platforms that will let you do exactly this with little manual effort. For example, target return-on-ad-spend (tROAS) in Google. They require a moderate level of marketing tech investment: you need to tell ad platforms what you expect the customer to be worth to you: i.e. what the “conversion value” is (which is the LTV, or lifetime value, calculated as the sum of future profits).

4. Do not blindly trust data reported by Google

Charlie Munger, the late partner of Warren Buffet, talked about incentives as a reliable way to predict outcomes. Google has just one incentive: for you to spend more money buying ads on their platform. So whatever reports they give you will, ultimately, have just one purpose: to convince you that your ad dollars are doing a GREAT job moving your business up and to the right.

That doesn’t mean that Google employees are intentionally doing something malicious, by the way. There are many other ways to end up with an incentive-optimized outcome that’s beyond the malicious route (some examples: prioritizing specific features; fixing certain bugs but not others; etc). So you need to form a view, independent of Google-reported data, about the efficiency of your Google spend.

Some metrics that Google reports are very easy to independently validate. Let’s say you’re running a Shopify-based store. If Google says that SEM drove 500 transactions, but Shopify only reports 200, that’d be quite problematic for Google’s reputation. So that typically does not happen - you can trust GA or Adwords-reported conversion numbers just fine.

But how about in-store visit data? Let’s say you’re running an ad campaign to drive customers to your clothing store. Google reports 500 visits coming from that campaign in the past week. How exactly did they determine that it was 500? Last I checked, Apple phones don’t send their geo-locations to Google 24x7… As you’d expect, Google’s methodology explanation is opaque; the logic is not easily verifiable. Only the most hard-headed quants will do the rigorous modeling necessary to validate these platform-reported numbers.

Sadly, most marketers aren’t even incentivized to do this kind of modeling: they instead get rewarded for taking “as much credit as possible” for whatever sales the company is bringing. In this case, physical store sales.

Lo and behold, it is possible to validate this data: by creating a model of what you expect relevant store sales to be without the “store visits” campaign; by calculating the amount of spend necessary to move that number by enough to cause a statistical difference; by doing this at a large enough scale, enough times, to have statistical confidence that the results are not caused by randomness.

Having gone through this with a client recently, I say “trust but verify.”

5. Experiment Every Week!

Those that think that SEM is a “set it and forget it” kind of program are missing out on quite a bit of value. There are many different levers that can be pulled within SEM to optimize performance; each lever impacts a different metric.

Trying to improve your ad click-thru-rate (CTR)? Test ad content.

Conversion rate too low? Experiment with the landing pages.

CPCs too high? Look at competitors, search queries, and Google trends to rule out obvious causes. Consider testing a new bidding strategy or keyword match type.

Test small using Google’s experiment tool when possible. Scale from there when statistical significance is reached.

Experiment with SEM beyond Google:

While only at 5-10% of the US market, Bing program is entirely additive / incremental to your Google efforts, because most users stick to one search engine. An easy way to launch Bing without much effort is to leverage the Google import tool and then optimize from there when resources allow.

If you have an app and you’re selling durable goods, Apple Search Ads is often a promising area to experiment, even though it requires a bit of martech investment to make app install attribution work correctly. For digital goods, “Apple tax” makes this less promising.

6. Hire experts and align incentives

SEM is technically quite complex; one of the aspects of that complexity is determining the right account structure. There are certain levers that can only be pulled at the campaign level (ex: bid strategy, location, device targeting). Others, at the ad group level. Your SEM channel owner needs to walk the fine line between “clear reporting/precise control” and having enough conversation volume to make the bidding effective. As such, having someone knowledgeable in both the intricacies of the business and the SEM craft is essential.

It’s tempting to have a single person running all of your paid media - especially if you're in a profitability crunch and your media spend isn’t huge. And yet, time and time again, I’ve discovered that it is virtually impossible to be a competent hands-on-keyboard channel manager of SEM and Paid Social at the same time. Each is just too technically complex, and is changing too rapidly to keep up with the details in both.

In all the brands that attempted this “let’s save money” route that I’ve seen, at least one of the major channels ended up having tremendous low-hanging fruit opportunities that were picked off within a couple months by a competent channel specialist. The ROI was obvious - in the millions in annualized returns.

I often get asked, “what if we cannot afford a full-time person to run this channel?” Then hire a part-time freelancer or an agency. Each will be a better option than leaving millions in spend essentially unattended.

If you have options, I personally recommend going with flat-fee operators (full-time employees or part-time freelancers) - as opposed to agencies that take a cut of spend. The reason, again, is incentives; the one that takes a cut is incentivized to see your spend grow - whether it’s effective or not.

Need some recommendations? Get in touch: [alex AT gotvocal DOT com].

More Growth Fundamentals

Check out the other articles in the recent Growth Fundamental series, in case you missed them: